Valor and Compassion

On Writing and Living

Know Your Plants!

Handling gorse may require heavy equipment (and it’s listed as a Weed of National Significance in Australia): Gorse management by the Victorian Gorse Task Force, http://www.vicgorsetaskforce.com.au.

Read-aloud time has always been crucial to surviving long trips in my family…along with hiking breaks every hour and a half, not to mention trips to the rest area. The other day, I was the designated reader and the whole family howled when I started a new chapter with the hero “lying motionless in a gorse bush.” Ouch! There’s no way you can lie motionless in gorse. It’s covered in prickers that act more like razor blades than thorns. I learned that the hard way years back, when we visited Oregon’s South Coast, where gorse has invaded many a state park. Native to the Iberian peninsula, Western Europe, and North Africa, the 20 species in the gorse (Ulex) family vary in height from foot-high dwarf furze (found on heaths in Great Britain) to ten feet high (as on the South Coast). On one hike, I thought I’d managed to avoid a slashing by staying in the middle of the trail through a gorse tunnel (pity the folks who cut through it!), but no! My sandal-clad foot recoiled from contact with a shoot emerging in the center of the trail.

Doubtless the author who’d situated his character in a gorse bush to spy had assumed the bush was an innocent inhabitant of the moors, not a bit player in a slasher film, but painful experience taught me differently. The moment reminded me of other passages I’d read in books where the writer hadn’t researched the plants that appeared in their stories, either as minor characters or as important plot points, such as ingredients in a healing potion or a poison. To paraphrase Dr. McCoy on Star Trek, “I’m a doctor, not a botanist,” but I’ve studied botanical medicine and local edible plants. You never know when a reader who picks up your book(s) might have a similar background.

Medicinal plant or alien being? Taster beware!

So here’s my distilled (or infused, or decocted) wisdom on using plants in your stories. If you’re a botanist, herbalist, or other plant wisdom-keeper, please feel free to share your comments and corrections. Also, please note that the information contained herein is meant to be tips for writing about herbs, not using them, and especially not to diagnose or treat any medical condition(s). To learn more about real-world uses of medicinal substances to treat your own ailments, please talk with your healthcare provider.

A tired old trope in fantasy fiction is the story that opens with a character picking medicinal herbs on her way back to her cottage. But what does this activity, and its associated knowledge base, entail? In preindustrial times, learning how to identify and use plants for food and medicine wasn’t necessarily the exclusive province of professional healers. Most everyone taught their children how to find and use plants to treat everyday ailments and injuries, with the more dangerous plants and rarer conditions being the province of the trained healer. Has your character received special training as an herbalist, surgeon, or battlefield medic? Or are they an ordinary rural village dweller who’s wood-wise? The latter might be most familiar with the nutritive class of medicinal plants, which are used as often for food as for medicine, have a gentle effect on mild ailments or injuries, and the recipient would grow tired of eating them long before they reached a toxic dose. Many of these beneficial plants are hardy and grow in abundance–i.e., they’re weeds. Some real-world examples include dandelions, burdock, chickweed, plantain, nettles, and mullein. Your character can find them easily on a walk just outside the village; they might even battle them as invaders in the vegetable garden, and thus weeding does double duty as harvesting.

These tomatoes may look wacky, but they’re harmless (and delicious).

Although these everyday plant medicines are usually mild in their actions, it’s still important to keep in mind that anything that heals can also injure or kill. It’s a common misconception that botanical medicine is harmless because it’s natural. Remember, though, that a substance can’t be both effective and harmless. If it works, it also has the potential to hurt somebody if they take too much, use it improperly, and/or are allergic to it. People’s tolerance to different substances varies greatly, which explains why some adults need a child’s dose of certain medications, while others might need enough to treat a horse. (Lots of possibilities for conflict in a novel abound here!)

On the other hand, toxic botanicals are medicinal plants that require knowledge and care to prescribe correctly. If taken in too big a dose (and there might be a narrow therapeutic window between treatment and toxicity), they can cause injury or death, and your characters won’t want to use them unless they have the condition(s) for which these plants are indicated. Naturally, this allows for potential drama, but it still needs to be realistic, well-informed drama. Some parts of the plant may be innocuous, while others are poisonous. Look-alike plants (and fungi) pose a different danger: one species is curative, while another that can “pass” for the helpful plant is either harmful or doesn’t do anything medicinally. And here’s something weird: some plants aren’t poisonous in themselves, but they grow in proximity to poisonous plants and absorb their dangerous compounds, for example, through the water when they grow together in marshes, and thus they become poisonous by contagion, as it were.

Some plants aren’t poisonous; they’re just darn unpleasant. It’s helpful to learn about their irritating qualities if you want to use them as plot points: plants with thorns or spikes, plants with oils that irritate the skin, and even plants that grow so densely that it takes a half-hour to bash your way through a half-mile thicket. (The shrubs growing around streams are often like this, which is one reason it’s harder to bushwhack along a stream bed than you might think. Following the watercourse isn’t always the best way to stay oriented.)

I recommend buying or borrowing plant-identification books for bioregions similar to the locations in which you’ll be setting your story: high desert, temperate rainforest, alpine area, etc. Even if you’re not writing alternative history about actual places, taking time to learn about regions with a similar ecology, geology, and plant life to your fantasy setting will make your descriptions all the more vivid, realistic, and in-depth. I suggest familiarizing yourself with the major plant families in these areas, along with their traditional uses and as much chemistry as you can stand. Although the plants with which you’re populating your imaginary realms may have fanciful names and features not found on Earth, learning some botany basics will make your creations seem plausible–and you’ll probably learn something nifty for a plot twist.

Some reference guides I use include Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast by Jim Pojar and Andy MacKinnon, Pacific Northwest Medicinal Plants by Scott Kloos, and Pacific Northwest Foraging by Douglas Deur. If you’d like to include fungi, check out David Arora’s comprehensive guide, Mushrooms Demystified and Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms by Paul Stamets. For inspiration for herbalist characters (on everything from the nuts-and-bolts of how they prepare their medicines to philosophical observations about human connections to the natural world), I recommend Healing Wise by Susun Weed and The Herbal Medicine Maker’s Handbook by James Green. I also love Robin Wall Kimmerer’s books, Gathering Moss and Braiding Sweetgrass. Dr. Kimmerer is a professor of environmental biology, and member of the Citizen Potawotami Nation, and her beautifully written books combine scientific/biomedical and Indigenous ways of knowing in an inspiring, informative way.

Luthien shows off a collection of king boletes (Boleta edulis) growing in the forest we steward.

Practical experience is the optimal way to conduct your research (just don’t nibble on any plant that you can’t identify!) Thus, my most important suggestion is to get outside and spend time with plants, accompanied by a knowledgeable guide (a person, book, or both). This will give you a truly holistic experience of the environments where plants grow, how they respond to that environment, and any plant “personality” characteristics that you’d only pick up through walking, or sitting, among them.

I hope this introduction inspires you to include the plant kingdom in your fictional worlds–and to let sleeping gorse lie (without lying in it yourself).

Luthien with a Western trillium (Trillium ovatum) left behind by a trail maintenance crew in Forest Park, Portland, OR.

Wounded or Waning Powers

Image courtesy of the National Council on Aging

Where have all the elders (or at least middle-aged folks) gone?

Literary and mainstream fiction are peopled by narrators of all ages (well, maybe not too many babies, but you know what I mean). Science fiction, and especially fantasy, feature some memorable older characters, but the genres lean toward youthful protagonists. Maybe this is because younger bodies endure adventures, battles, and such with more resilience than older bodies. In addition, quests for some external goal dovetail well with the Bildungsroman conceit of a young person coming of age and discovering themselves. Elders end up as advisers to the strapping heroes, or the Evil Dude/Dudette is of advanced years. (The wicked queen in Snow White is the archetypal example: now that she’s no longer young, she’s supposedly lost her most salient feature–her beauty–and goes in for a vendetta against the “fairest of them all” who’s supplanted her.)

One feature that distinguishes exceptional SF and F novels from the rest of the pack is when the author presents us with imaginative yet realistic and believable non-human sentient species. Sometimes, with the plethora of books out there that center on young protagonists, older main characters seem to have become an alien species of their own…and kudos should go to writers who foreground them.

I enjoy writing about people (or other sentient beings) who’ve already lived a full life before the story begins. Their backstories become the personal version of world-building: just as the setting radiates a rich, textured feeling when the writer does their world-building homework, a character with a backstory exudes complexity, and yet how much backstory can somebody have when they haven’t lived very long? Of course, I’m not suggesting that young characters are uninteresting, unintelligent, unwise, or otherwise tabulae rasa, but they bring other gifts to the story–such as idealism, intensity, and passion–that become even more engaging when they interact with an older character who’s more than just the guy at the inn warning the youngster about the monster over the next ridge. (And I must confess, it’s become easier for me to speak through a middle-aged character than to dredge up from the now-grayer gray matter what it felt like to be sixteen.)

Knights of a certain age.

Take a peek back at one of your favorite novels (or series) and notice how most of the time, the writer drops you right into the middle of events, with information sprinkled skillfully to orient the reader so they can get absorbed without getting confused. Now think about the interesting angles you can create when you drop the reader into the middle of a narrator’s life. Here’s someone whose story has already been going on for a while, allowing the opportunity not just for fast pacing and excitement, but also for the intellectual, sensory, and emotional feast of a long, challenging, adventuresome life and the personality to go with it.

In addition, your older narrator’s characteristics have had time to harden into place in a way that a more malleable younger person’s haven’t. This means they’ve honed their talents, skills, and strengths, but it also means they’ve had more time for their flaws to deepen–and a flawed character is not just interesting and believable but also apt to make decisions that intensify conflicts and get them in trouble, which is where you (and the reader) want that character to be to keep the story chugging along.

However, here’s a word of caution against reinforcing ageist stereotypes about either old or young characters. Don’t forget to surprise your reader (and other characters) when your older protagonist goes against “type” or violates the expectations of family and community members who’ve come to expect a certain behavior pattern. Maybe an elder who seems stodgy, who hasn’t left the village in thirty years, answers the call to adventure again, and their grandchildren watch as they shake out a dusty old traveling cloak folded in a trunk under the bed; with a spring in their step, they head for the door to finish something they’d started decades before.

Struggling with a stiffer, less strong, more balky body makes for a poignant “person against self” conflict too. Sore knees at the end of a long walk (or sore thighs after a long horseback ride, or sore everything after a long trip on a cart or coach–those things had little to no suspension, and roads were rough, in the preindustrial eras that usually inspire fantasy fiction) remind elder heroes of their mortality. A knight or warrior coming out of retirement for another adventure might notice aches and pains from old battle wounds, and they might lament their slower reaction time even as they commend themselves for more mature strategy and tactics (as well as patience and a willingness to try for a diplomatic solution rather than the “slash and bash” approach of their youth). And what about magic-users: do their abilities decline with age even as their wisdom and skill deepen? How might their more advanced years impact their ability to recover from using magic?

Wizards don’t get older; they just get wilier.

So many characters in the speculative-fiction realm set out on journeys of self-discovery at the same time as they take responsibility for the fate of the world, but older individuals’ work as mentors, guides, and elder states-beings can be just as compelling. Elders in fiction provide inspiration and insight (as well as a glimpse of the future that doesn’t have to involve dread or embarrassment) for younger readers, and readers who’ve stayed loyal to the SF and F genres can recognize what might be a universal experience of growing in authority and sagacity even if their physical powers are declining–whether we’ve got fingers, fangs, wings, or suction cups.

For inspiration, here are some SF/F novels with middle-aged or elderly protagonists:

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Gandalf may be millennia old, but Frodo and Sam also aren’t spring chickens!

The Face in the Frost by John Bellairs: An under-appreciated classic with charming elderly wizards.

Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock: Rich mythopoeic fantasy series with many older characters

Order of Valen and Order of Collegia Magica series by Carol Berg: Wonderful, lyrical writing and great characters who’ve been worn and battered by life.

WRITING Around The Edges

I used to belong to the most amazing writing-critique group. We had all the ingredients for an effective and supportive group. Our five members were not too many for a personalized approach and not too few to supply something to read at each monthly meeting. We all wrote in the same genre (science fiction and fantasy), so we didn’t have to explain genre conventions like faster-than-light space travel and instantaneous interplanetary communication. We all wrote novels, which requires a different critiquing approach to short stories. We were also committed to being both honest and kind in our critiques. And best of all, we just enjoyed one another’s company. We laughed together all the time about everything from unintentional writing bloopers (you know, everything from extra hands to the right gadget, or even divine intervention, showing up when you need them to) to life’s wackiness in general.

We started out meeting in bookstore cafes, but then we discovered the most remarkable venue: our local writers’ group, the Willamette Writers, had purchased a house that they dubbed the Writers’ House, where members can rent a room for the day and…well, write! Each room had a theme, from children’s literature to whodunits. Our group would decide on a day every month or two and we’d rent the whole house. It was so exciting to arrive, equipped with water bottles, laptops, research materials, and snacks, greet one another, catch up, and pick out our rooms–like a sleepover for adults! Then we’d go off to our spots and write until lunchtime, whereupon we’d stroll down the street, gabbling about what we’d created so far, and have lunch at a local restaurant. I know it’s cliched to describe an atmosphere as electrical, but that’s the best way I can capture the sheer animation, the joy and excitement, of sitting together and bouncing ideas off one another. Even being in the same building with other writers, despite concentrating on one’s own projects, galvanized each member’s creativity. After lunch, we’d head back, write some more, and then spend an hour or two at the end critiquing before having dinner together and returning home.

That was an incredible time of fellowship and shared inspiration. I’m so grateful for the experience and the camaraderie. Thank you, Teri, Tonya, Rob, and Tom!

Then, about eight years ago, our group drifted apart–not because we had a sudden blowup but because for different reasons, writing started taking a back seat to other aspects of life. One member was hired for a dream job he knew he’d love, but it also demanded time that he used to devote to writing. A second member’s two children had reached the age when extracurricular activities start to assume control of the family calendar, and he found himself enjoying attending and/or participating in these activities with them. I was expecting my daughter, and just when the intensity of parenting a young child was starting to ease off, first my father and then my mother began to require my spouse, my brother, and me to assume elder-care duties. I often think of my dear writing friends and hope that when some of these responsibilities loosen a bit, we can get back together to talk about rebuilding our group (or just rekindle the friendships).

But then, first we’ll each need to have written something to share, and while I can’t speak for the rest of us, I know I haven’t got anything ready.

Advice abounds on how to carve out more time for writing in your life. Unfortunately, sometimes it comes with a scolding, guilt-inducing tone along the lines of “Writer X worked 60 hours a week as a bus driver, and yet she managed to become a bestselling author. If you’re that passionate about writing, you’ll find a way.” That may be true, but depending on how oversubscribed one is, that way might involve a major sacrifice: adequate sleep, relationships, fulfilling work (as opposed to work that might fit around the edges of one’s writing but is uninspiring and difficult).

In my experience, external impediments to writing come in three forms: organizational problems, inaccurate assumptions about what one needs (environment, tools, etc.) to write, and work/family obligations. The first two are fixable; the third requires either enlisting more support or making peace with the decision to modify one’s writing and publishing goals until one’s season in life changes due to a combination of changes in circumstances and internal changes (attitude, motivation, etc.)

Organizational problems can involve one or both aspects of the space-time continuum. Maybe your physical space is too tiny to establish a writing territory that’s out of bounds to feline, canine, or human family members. Maybe even if you create a home office for writing, you can still hear your teen’s music reverberating through the walls. Perhaps clutter disrupts your focus, but finding time to clean is a hurdle in itself. Perhaps you experience challenges with structuring the free time you have, or you experience mission creep from work or family activities: you end up taking a work project home, or a meeting for which you’d budgeted an hour sprawls out into three. Urgent matters have an obnoxious tendency to crop up at the last minute. Argh!

Some of these organizational matters are beyond your control (like the school bake sale your child doesn’t tell you about until the night before, along with the lovely fact that they’d signed you up to bake cookies for 200 and the last time you baked something was when you were a preschooler cooking play-dough in one of those play ovens). A multitude of materials exist for helping people to achieve greater organization and efficiency, promising to liberate you from the physical and mental clutter that clogs our days like hairballs in drains, freeing your creative energy to flow. (Sorry about the creepy plumbing image there.) All right, maybe these resources won’t solve all of your organizational challenges any more than self-help books will magically transform you into a more enlightened, lovable, date-able human being, but it’s worth your spacetime to pick out what might work for you so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel (or the word processor, or the writing space). Advice from other writers is particularly salient. Be on the lookout for ones who have or are experiencing similar dilemmas to yours (writing with a chronic illness, writing while caring for children and/or elders, writing when you work long hours, etc.)

Next comes the expectation department. In Buddhist thought, we create our own suffering by having expectations and then becoming disappointed when real life falls short. A few years ago, I went to look at a piano for my daughter–the seller was willing to part with it inexpensively, as she was moving soon and it was the last item that had to leave before she put her house on the market. When I arrived, I discovered the most gorgeous house imaginable, with a panoramic view of the ocean and my dream writing space: a top floor consisting of a single room with windows on all four sides. The only problem proved to be a huge one: um, I didn’t have several million dollars to buy that house!

I’ve long envied writers who could go to a busy cafe, park themselves with a meal and a cup of coffee, and spend a couple of hours writing. All that lively energy surrounding me would be distracting, not inspiring. I’ve discovered that I can’t write in train stations, hospital waiting areas, the Department of Motor Vehicles, or any other place where you’re forced to wait for something long enough that you could (theoretically) crank out a few pages. When I say “can’t,” I don’t mean I haven’t tried…I mean my brain doesn’t work that way. Distractions are deadly to me. However, I’ve come to a compromise with my poor brain: I’ve learned to accept the “good-enough” space, just like my sweet daughters have learned to accept me as a “good-enough parent,” to borrow D.W. Winnicott’s memorable phrase. If I can find an out-of-the-way nook in, say, an airport arrivals seating area, I can at least create an outline or edit something I’ve written in my better, more conducive writing space at home. I’ve discovered that not every writing task demands the same level of concentration, and also that as long as I have quiet and minimal distractions in the crucial first half-hour of a writing session, a culinary bomb can go off in the kitchen–or my seven-year-old can wake up and dance around the living room near me–and I can keep going long enough to wrap up my idea and sketch out a plan for the rest when a better spacetime situation arises.

If you wait until inspiration arises to write, you’re not going to spend much time writing. If you wait until you’ve created the perfect writing space, or you can afford to go on writing retreats every weekend, or you’re retired and your children are grown, then you’ll either never write or you’ll complete a total of five glorious pages.

The last impediment, work/family obligations, is the most obdurate. Some aspects of life are non-negotiable. Children need parents; in the contemporary world, unless you’ve inherited a trust fund that will last your lifetime, adults need incomes; your friends and family need your presence, your love, and your attention. As publishing professional Jane Friedman reminds us, some writers managed their output at the cost of important relationships: they were absentee spouses and parents who tossed other family members the bone of an acknowledgement at the back of their latest book. (I encourage you to read Jane’s blog post “3 Principles for Finding Time To Write,” September 25, 2018: https://www.janefriedman.com/finding-time-to-write/).

One of my friends is a minister, and when I confided in her about my struggle to write while being a physician, parent, and caregiver to an octogenarian parent with a disabling condition, she gave me a gentle, priceless reminder: “All things come in their seasons. Maybe this isn’t your writing season.” I couldn’t envision not writing–it’s my life’s blood, my breath–but I could adjust my expectations to work on editing existing writing for publication, composing poetry, producing the monthly columns I write on health and bicycling for my local newspaper, and other projects that don’t demand as much unbroken time. I strive to redefine these activities as exercises that keep my “writing muscles” healthy, build a platform for eventual traditional publication, and create connections with other folks in the profession.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created its own special problems for me and other writers. As a physician, I’m defined as an essential worker. During our state shutdown, what might’ve been an ideal time to work on my new novel ended up being a hectic time when I was needed in my community more than ever. Yet I’m also aware that friends who did stay home encountered other obstacles: for example, having school-aged children at home with them and needing to supervise their homework packets and online class meetings. (I had to do these things too…at work.) As the situation continues to evolve, I’ll be spending most of my time helping my patients, partnering with my spouse to care for our family, and trying to stay healthy myself. This extra workload (and care-load) has eliminated my major means to keep writing consistently: getting up early to put in a few hours at the computer before anyone else wakes up. Simply put, I’m too wiped out to get out of bed until I absolutely must. Yet I feel obligated, not just to do my work, but also to create and to connect, to lift up and to celebrate, which I do through writing. I fear I’ve missed the opportunity to provide others with an escape, a pleasure, and food for thought during a difficult, isolating time.

That’s why I’ve pledged to return to this blog after a long hiatus. Even if I’m strained to find time to plug away at my next chapter, at least I can reach out to others who miss browsing in a bookstore, listening to a writer reading their work in an actual physical meeting room, or hanging out with their writing buddies. Beautiful writers and readers, let’s make a new start.

Thanks to Seth Goldstein and Luthien McDonald-Goldstein for making an appearance in these photos.

Writing Saved My Life

Mysterious lake, courtesy of freeimages.com

Writing saved my life.

Reflecting on the year-plus I’ve spent intermittently tending to this blog, I notice I’ve spent my time addressing challenges in world-building and character development, but I’ve danced around the heart of it: what inspires somebody to write at all, and the way that writing grows a person at the same time as the writing grows.

People choose writing as a means of expression, or writing chooses them as a conduit for the universe’s own creativity, for many reasons. In offering mine, I’m describing, not prescribing. In particular, I don’t believe that one must be wounded and suffer to be a writer (or any other artist), and not all writing must serve as therapy. Yet long before writing became an enjoyable act for me, it started out as salvation.

Emily Dickinson describes the poet as a “Soul at the White Heat.” On the surface, Dickinson appeared conventional, her reclusiveness an extreme but not unheard-of manifestation of the gender script for upper middle class white women in the 19th century. She toyed with social expectations in describing herself as “small” and “Nobody,” but she also presents herself in her poems as a volcano erupting and her life as “swell[ing]…like horizons.” She might have occupied a small space in her family’s home, rarely traveling beyond her town, but the power of her imagination expanded her beyond the restrictions imposed by her time and culture.

Digitized image of Emily Dickinson’s Poem #162, courtesy of the Emily Dickinson Archive: https://www.edickinson.org/editions/2/image_sets/78748

For different reasons, I remember being “small” and “nobody” as a child, not because social expectations confined me to tiny places, but because I did what I’d witnessed other creatures do when overwhelmed by fear: squeeze into a snug hideout until the danger passed. Ironically, I’m claustrophobic, so I’d never crawl under the bed or close the closet door on myself, but with the best understanding I possessed at the time, I convinced myself that shrinking my selfhood to its most compact form would keep me invisible and therefore impervious to further harm.

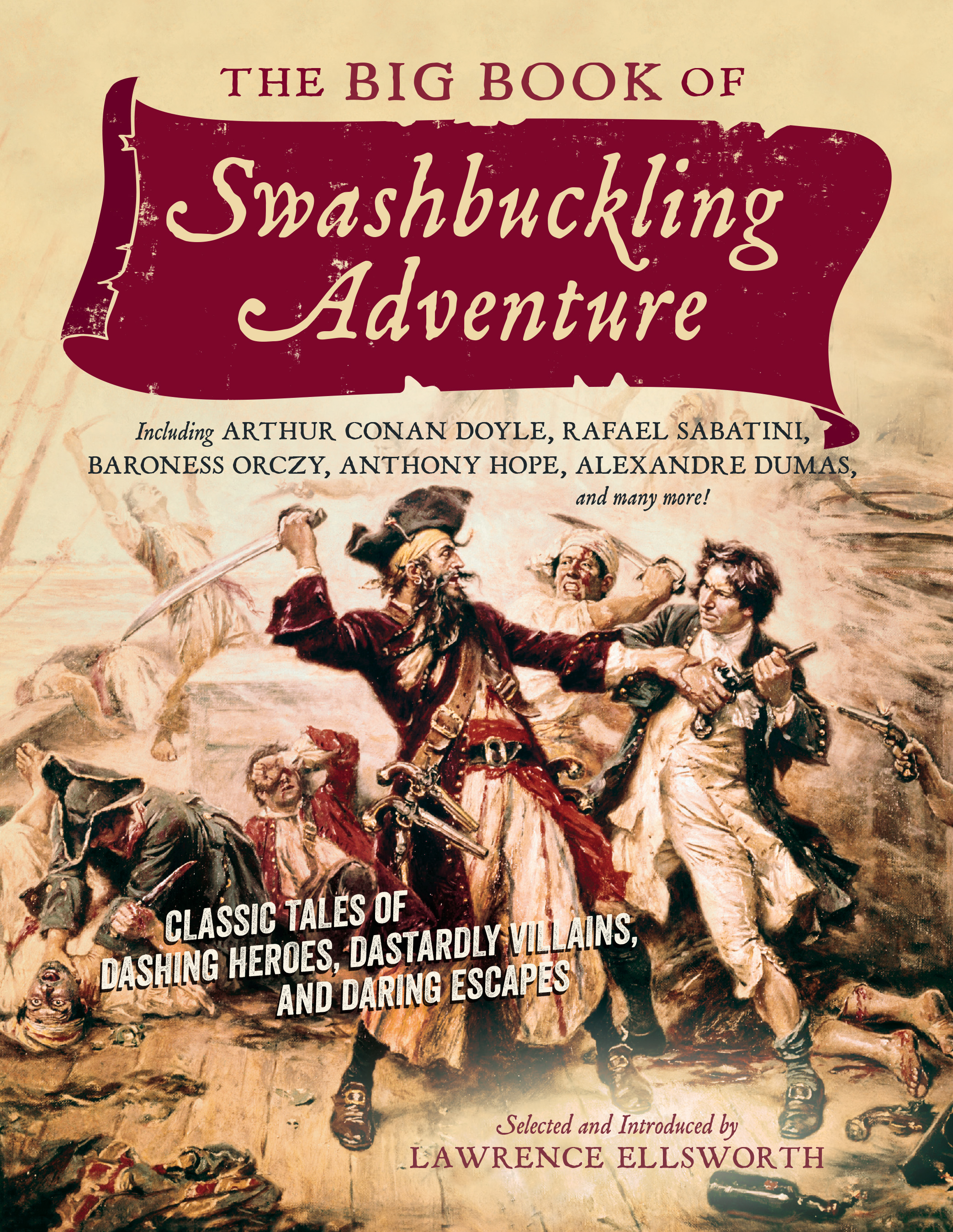

As soon as I could decipher words for myself, I wrapped myself in books as if taking refuge in a cave made of words and imagination. I presumed many writers experienced life the way I did, as lonely and excluded oddballs, since so many characters in children’s books endured torments from their peers. But the books I loved best weren’t the ones where I could identify with an isolated, hurting kid in the real world, but fantasy worlds where young people swashbuckled or cast spells, being active agents in their worlds rather than suffering at the hands of all-powerful others they couldn’t escape.

Now that’s more like it! Laurel Masse at laurelmasse.typepad.com

At some point, my word-space expanded to including writing. When creating my imaginary realms, I experienced power I lacked in the real world. I could determine outcomes; I could transform mice into lions–or better yet, giant mice who triumphed over predators. In envisioning ways out for trapped characters, eventually I wrote my way to choices, and power, for myself in the world outside the page.

Writing allowed me to tell my story in a way that healed rather than retraumatized me. I could distance myself from my experiences by changing the specifics, by causing them to happen to a character rather than me (distancing myself at the same time as I “wrote what I knew”), and by transforming the outcome. Maybe the character got out of the situation, emerging from a brush with harm rather than undergoing the damage. Maybe the character was older than I was at the time when I wrote their story, and the events had happened in a safer, more distant past, and they had grown into a strong, assertive person, a warrior with an honorable battle scar, no longer the walking wounded. All the while, I could talk about suffering without living through it again, wading back ashore instead of flailing around in deep water, drowning.

Writing did something else for me I hadn’t recognized until recently: through telling my story as a narrator’s, I unwittingly–but perhaps with some inner wisdom–gave them dysfunctional coping methods that I therefore did not have to enact in real life. From my reading in medical school about survivors of adverse childhood experiences, my situation, personality, and coping styles all would’ve predisposed me to developing an eating disorder, and yet I never did. However, when I look at the illustrations that accompanied my earliest stories, my protagonists all looked like they had anorexia nervosa: thin to the point of emaciation, which I described in a positive light, as if this stick-thin form were my ideal body–a saintly one, in my view. (At the same time, I’d read a book on Catholic saints and became fascinated with their self-denial, which included long fasts an ordinary person wouldn’t survive, so I had historical precedent for canonizing characters who were on their way to becoming disembodied.) On the rare occasions I described these protagonists eating, I praised their “bird-like” appetites and distaste for embodied reality in general. It’s as if in describing my characters this way, I spared myself from developing the condition. Controlling my characters’ body shape and food intake prevented me from acting on the compulsion to control my own.

Writing saved my life.

I’m a private person and hesitate to share this. I’m not as comfortable as my patients in recovery are, who courageously share that they are recovering; I’d rather stay quiet about the disturbing stuff, both because of my characteristic interiority and because I hesitate to trigger anyone else’s pain. And yet I find that this very reticence is what’s been holding me back from taking that final step toward securing representation and offering my work to a wider readership than the two regional outlets I write for. My characters aren’t “me” anymore, but like many writers, I offer myself on the page…and that’s scary.

Admitting what has nudged me closer to the “white heat” of the writer’s soul-fire, I feel and hope, will dissolve that last barrier, my own reluctance to draw the screen away from the flames, and to welcome others to sit around my fire where I invite them, you, to speak, to listen, to be affirmed, or to warm your hands and yourself, and to see by.

Disabilities and Possibilities: Characters with Disabilities in SF and Fantasy

Children (one on foot, one in a wheelchair) careen down a steep slope.

Erica Meza, “Disability,” https://www.booktrust.org.uk/news-and-features/features/2018/december/the-one-in-the-wheelchair–a-look-at-childrens-books-and-disability2/

Lately, I’ve noticed a long-overdue trend, in various genres, where a story’s central character experiences life with a disabling condition. As a science fiction and fantasy writer, I’m also excited about the possibilities for writing disability in either preindustrial or advanced-technological settings, or among alien species for whom “disability” may imply something different and thought-provoking. With its core intention to explore futures-that-might-be, science fiction is a literature of the possible, and this raises intriguing questions—ethical as well as scientific and technological—about living with disabilities.

The subject is personal as well as conceptual for me. Both of my parents were special-education teachers in New York City public schools. My mother taught Resource Room, a supplemental instructional service where children came to her classroom for an hour each day for additional support with reading, writing, and/or mathematics. My father taught at a school for children and adolescents with profound physically and/or mentally disabling conditions. Since my brother’s and my school holidays didn’t always coincide with our parents’, we’d come to work with Dad on these days. Because of our parents’ work, we developed respect for human variation and the ways people worked with and around their limits—limits that we all have.

In my early twenties, my awareness expanded to less visible impairments, such as the mental-health conditions that affected me and other family members: anxiety, depression, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. (I still wince when I hear people casually toss out things like, “Oh, he’s so OCD” to describe someone who’s just fussy, who may be annoying to get along with but who doesn’t spend an hour checking and re-checking that the cat hasn’t followed them out of the house and is now locked out on the porch.) Then, as I grew older, people close to me developed either age- or injury-related conditions that impact their lives. My spouse has a mobility impairment from a car crash, using a cane for balance and living with chronic pain. My mother has multiple sclerosis and now depends on her wheelchair to get around.

I mention all this not just to provide “I’ve been there” bona fides, but also because I’ve witnessed a backlash against efforts at inclusivity in stories. You’ve heard these criticisms: that writing diverse characters is “politically correct,” a passing fad, and/or just window dressing that doesn’t advance real acceptance or change.

I’m not suggesting that you include a character with a disability as a “token” or because it’s hip. Readers will see through this and won’t appreciate it. But consider this: one of the most liberating experiences anyone can have is to encounter someone like themselves as the protagonist of a story. Conversely, it’s disempowering when, instead of finding characters who look, sound, think, move, behave, and dream like them, readers find absences. You know you exist, but when you don’t find yourself reflected in books, you internalize the notion that your story doesn’t matter; you don’t matter. This realization is particularly acute for young readers just coming to understand their place (or lack of it) in the world.

The bottom line: if it feels like an imposition to “give” a character a disability to advance some agenda or because it’s fashionable, follow your instinct and don’t do it. But if you’d like to write about a character with a disability, here are some general suggestions and then a few thoughts about science fiction and fantasy in particular.

In writing a disabled character, you tread a tightrope between making their disability everything or nothing. It’s a significant part of life, but it isn’t the person’s sole identifying feature. Yet it’s also too easy to forget the character’s limitations when it’s inconvenient. This isn’t just true of disabilities. How about that character who survived a sword cut to his leg in Chapter 2 and by Chapter 3, he’s back to his daily run without time off to heal or lingering debility? Or what about the character whose mother just died and, other than the immediate shock, isn’t shown mourning and adjusting to the loss in subsequent scenes?

You’ll need to give this character a full life, with interests, skills, desires, hopes, and impactful experiences, as you would for any other character. Yet it’s also important to think about how their condition affects both their daily life and the decisions that drive the story. Research is vital: reading and watching documentaries about the condition, talking with someone who has it, and testing things out physically yourself, if you don’t have the condition—such as borrowing a wheelchair and experiencing what it’s like to ride the bus, go into a restaurant or bank, do your work, and interact with others from this position. If you have the condition yourself, then you have a rich fund of lived experiences to draw from, but it would still help to do the medical, psychological, or other research, especially if the science associated with the disability will be an important part of your story.

If you’re writing a fantasy novel, it’s most likely that you’ve set it in a preindustrial world. What hurdles might your character have to face? What technologies would be unavailable to them, and even with some technical assistance, does this character face other barriers, such as the cost of purchasing assistive devices? Would your world’s magic system provide the character with assistance that technology might offer in ours?

Or is magic implicated in the character’s condition? This might mean a spell that causes the character to lose their sight or a limb, or the price of magic in general. As the venerable fantasy writer Orson Scott Card has lamented, too often, magic-using characters wield these amazing powers and never pay a price. They do stuff that—let’s face it—violates the laws of physics, and they don’t end up drained, suffering from a migraine, hungry, or even feared or ostracized. What has your character sacrificed in return for their magic? There’s a long tradition in many cultures where a magic user is also impaired in some way; a crippling injury or birth defect might even be interpreted as a sign of divine favor. Is this the case for your character? Or is there just a huge, and fascinating, contrast between their impairment and their impressive psychic power? That combination of strength and vulnerability, in whatever form each takes, makes for compelling reading.

How does the society in which your character lives react to them? Without the benefit of scientific explanations, what assumptions, or even superstitions, might community members entertain about them? These can run the gamut; it’s more interesting if the other characters don’t all respond in the same way. One person might insist that the protagonist’s withered arm marks him as the Evil God’s representative; another might feel sorry for them in a self-serving way; another might be a friend and supporter who sees past the disability to the person. Reactions to the character can also change when they change locations. They may be feared or reviled in their own village, but over the border in another land, their distinctiveness may make them revered, or folks in the big city a half-day’s ride away may not even notice them.

If the society in which this character lives is resource-strapped, poverty-stricken, and beset by an extreme climate, would that mean some community members view this character as a burden on their family or the whole group? Maybe influential people pressure the character to leave the community in a time of scarcity and this is the impetus for their adventures to begin. On the other hand, I think it’s important to be aware that even in communities where desperate conditions prevailed, individuals with disabilities were just as often cherished. I remember reading about a Neanderthal skeleton that showed evidence of a congenital disease that would’ve required others to carry him from place to place and assist with his personal needs. He’d been buried with care and his skeleton suggested he’d lived into middle age, evidence that he was a valued community member, not a “burden” to be discarded at a time many of us view according to the “survival of the fittest” mode. Being rejected by one’s community makes for great conflict, but it’s good to keep in the back of one’s mind that rejection has not always been the default reaction to people with disabilities in the ancient world.

The advanced technology that’s the baseline for science-fiction stories offers a different challenge for the writer: why hasn’t the biomedical tech “fixed” a disabled character? Maybe they have a problem with accessing these resources: if they’re poor or otherwise disenfranchised, the technology to cure their condition is beyond their means, and that in itself might drive the plot. Or might the character have a reason to refuse treatment? Does their disability come with a talent or favored feature that they’d lose if they were cured? Does their culture of origin value either the disability itself, or some ability that comes with it, enough to discourage repairing it? Might the person view their condition as a part of their identity and others with the same condition as part of their culture? If the person belongs to an alien species, would something a human reader might view as a disability be an advantage, a privilege, or a gift instead?

Perhaps the available technology can’t remedy the disabling condition, but like awesome magical powers might do for them in a fantasy novel, it might offer compensations. Perhaps the character exerts power and experiences freedom in a virtual space while their physical self retains its limitations in real space. Does this person wield great influence in a virtual space, anything from a holographic alternate reality (like a game) to the world of high finance, dependent on virtual transactions?

Creating a character with a disabling condition can provoke reflections on the limitations we all experience. When the writer fashions such a character with skill, empathy, and realism, as they make their way through their world(s), negotiating around the hurdles and drawing from their strengths, readers recognize a connection with them, for that’s what we all do. Still, it’s important to remember that the character is a person first, not a symbol or an inspirational figure. Don’t forget the value of a light touch. The character most likely doesn’t waste time feeling sorry for themselves—and neither should the reader, or you.

Fighting the Good (or at least believable) Fight

Image Credit: campaignlive.co.uk

This morning, I was reading aloud (to my spouse and younger daughter) a hilarious article in my favorite magazine, Backpacker, where readers described the craziest things they or someone else took into the backcountry. When I got to the piece de resistance, somebody lugging a broadsword on the Pacific Crest Trail (they didn’t mention if the bearer was also dressed in period costume), my spouse stopped laughing. The writer presumed the sword weighed in between 40 and 50 pounds. “No way,” Seth said. “That sword would be ten pounds, tops.”

Seth is an antique-sword aficionado and has hefted his share of blades at Renaissance fairs and science-fiction conventions, but just to be sure, I inquired of the Internet Oracle how much a broadsword weighed. Not only was Seth correct when it comes to this persistent myth about unwieldy old swords, but the swords proved even lighter than he’d estimated. According to experts (a museum professional, a sword-maker, a fight choreographer, and a historian) cited by the Association for Renaissance Martial Arts, even outsized weapons like broadswords tipped the scales between 3 and 6 pounds. Ceremonial blades might weigh more–up to 8 pounds–but they weren’t intended for wielding in battle (J. Clements, “What Did Historical Swords Weigh?”, The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts, accessed online on April 8, 2019: http://www.thearma.org/essays/weights.htm#.XKvDOJhKjIU).

While I agree with that Backpacker reader that reproduction swords aren’t ideal weight- and space-saving items for a backpacking trip (not to mention that I’d prefer not to go armed into the wilderness), but my pack is still many times heavier.

Fight scenes occur in many genres, but I’ll focus here on mine, fantasy (for which they are a staple) and science fiction. Although an implausible fight scene may not make or break your book’s chances of being published, it will surely cause knowledgeable readers to howl and will draw them out of the story.

Back in my twenties, I studied Ninja Taijutsu, including Kendo (sword form). While I remain a novice hobbyist, my years practicing martial arts have provided me with knowledge that makes it hard for me to endure certain (erroneous) conventions when it comes to swords-and-sorcery combat scenes. While my focus will be on common mistakes in scenes where sword-fighting or unarmed combat occur, I hope my advice can translate to other types of fight scenes you might include in your book.

So here they are, my top five combat mistakes appearing in fantasy novels:

Image credit: historicalnovelsociety.org

The swashbuckling conversation:

I took part in a critique session at a writer’s conference two years ago where everyone in the group reviewed and made suggestions about the first page of one another’s novels. One writer began her fantasy novel with a sparring scene. The dialog sparkled; the character dynamics flashed; the pace clipped along; the central conflict was nested in the interactions rather than in tendentious exposition. There was one one problem. The two characters–sparring partners, friends, and potential love interests–conversed while engaged in sword practice, without sweating, breathing hard, missing a conversational beat, or getting distracted enough to trip or fail to avoid a whack to the side.

A variation on this theme is the climactic sword fight (or boxing match) where the protagonist and the antagonist fence with both words and swords and manage to excel at both. A sword may not weigh 50 pounds, but wielding one is still effortful. Renaissance fighting-arts experts I’ve met admit that they can keep up this kind of maximal effort for maybe ten to fifteen minutes, less in armor.

The bottom line: feel free to intersperse your fight scene with dialog, but make sure to show the physical toll the fight takes on the opponents: breathing hard, sweating, damp hair getting into eyes, wounds stinging at the very least…and the words should come in bursts, not fluid paragraphs.

Image credit: listverse.com

Taking on multiple opponents:

Another problem I come across, both in published books and in books I’ve been asked to critique before the writer goes in search of an agent, is that iconic scene where a character holds off three or more opponents who come at them at the same time. It’s a chance for the protagonist to showcase their awesome skills–and it’s not believable. As one martial-arts teacher I know put it, “If more than one person threatens to attack you, the best thing to do is run away.”

A chase scene could prove to be cool in its own right, and it could advance the plot in unanticipated ways (the character stumbles into a new place that turns out to be important, an unexpected ally appears, etc.) But if you don’t want the character to run away, here are a couple of ways to even the odds more realistically when one goes up against an angry crowd.

Use the terrain. One of the most famous battles of classical times occurred at Thermopylae, where the ancient Greeks held a narrow area between a steep slope and the ocean, forcing their adversaries from Persia to come through in small numbers. Although the Persians outnumbered the Greeks, that tight squeeze effectively reversed this advantage. Similarly, a wily protagonist can lure the attackers toward a spot they can guard, where the multiple adversaries must approach one at a time, thus eliminating the advantage of numbers.

Alternatively, put obstacles between the protagonist and the attacking horde. If the area doesn’t offer a hiding spot, the protagonist can still delay the attackers by getting large objects between them: machines, transports, etc. They can also hurl things at the attackers to divide their forces, inflict injury at a distance, and such, keeping the pack from closing in.

This brings me to the importance of choreography. Whether it’s a battle scene, a pursuit, or just a meeting, it helps to set up your scene physically. You’ll know where everyone is in relationship to one another, the setting, and important objects, as well as if a character has the time and space to perform an action you’re describing. Don’t hesitate to act it out and make sure it works. (Never mind that it’s fun too!)

Image credit: “Arm Wrestling Kitten,” flickr.com

Sudden skill:

Picture this scene: Jeff, a big, placid son of a farmer and the protagonist of your story, is hanging out in the local tavern when a stranger starts harassing his friend Chella the bar maid. She turns down the stranger’s overtures and he grabs her arm. Enraged on his friend’s behalf, Jeff, who’s never been a fighter, launches himself at the nasty dude and fisticuffs ensue. To his amazement, Jeff discovers he’s a natural fighter and overcomes the vile stranger (a seasoned street brawler), to the applause of everyone in the tavern.

As satisfying as this situation might be to both Jeff and the reader, it’s not believable for someone who’s never studied unarmed combat to discover cool moves on the fly and best an opponent. I asked some martial-arts teachers about whether they’d ever had to apply their training to a real-life altercation, and those who had inevitably revealed, with some chagrin, how easily all that practicing vanishes from one’s head when flooded with real fear. That’s why everyone from martial artists to emergency responders drill their skills so often, in the hopes that it’ll come as second nature in an emergency. Yet, if someone who’s studied martial arts for years can panic and forget everything they’ve learned in a moment of terror, how much harder it would be for a neophyte to turn into a fighting machine with no prior preparation.

More realistically, you could send Jeff help in the form of a few tavern patrons and Chella herself, and perhaps he can get in the decisive blow that sends the horrible stranger skidding across the bar on his back. You can also make use of advantages Jeff does have–such as his greater size and strength–and make him come out a hero without having to channel Inigo Montoya.

Image credit: “Dodge Arrows Fabulously,” Amino Apps

Only the antagonists are bad shots:

Anywhere distance weaponry appears (bows and arrows, laser pistols, cannons, throwing knives, etc.), you can find this goof. Movies are particular offenders: the good guys/gals run the gauntlet past enemy soldiers, yet while arrows or laser blasts rain down around them, they never connect with their targets. Either the heroes are amazing at dodging or the baddies are chosen for their abysmal marksmanship. The protagonist, however, manages to squeeze off a casual shot that ricochets off a wall and knocks a sniper into a chasm. What’s the deal? Did all those bad guys/gals graduate from the same ineffective boot camp, or is their poor aim a form of deus ex machina?

It’s understandable that the writer intends to get their heroes through the book (or movie) alive, but too much good luck ceases to be believable. Somebody needs to experience a narrow escape, a wound, and where the stakes are highest, the story may necessitate a sacrifice, where a beloved character dies, and no, not the red shirt–that’s cheating. The character needs to be important enough, and sympathetic enough, that the reader laments their passing. You don’t want to go too far the other way and make the character’s death gratuitous either. Real life abounds in senseless outcomes, but in stories, readers expect painful situations to be meaningful, to accomplish a worthwhile goal, even at great cost.

Image credit: “Apollo Gets Swallowed Up By Black Hole,” maddlyodd.com

Rising up to fight again:

This last fictional fighting flub irks me as a physician, not just a perpetual beginner with martial arts. In both books and movies, characters survive injuries that would either disable or kill them in real life. Severe concussions, a kick to the kidneys, a strike to the spleen, getting shot in vital spots–sure, when adrenaline takes over, you might not feel that laceration right away, but at the very least, the blood dripping into your eyes should compromise your ability to judge and respond to what’s coming at you next.

Whether it’s a penetrating wound such as a spear thrust or impalement with an arrow, or a slash from a sword or other edged weapon, injuries compromise muscle, nerve, and blood vessel function. If you’ve got an arrow sticking out of your shoulder, it’s likely severed nerves and you can’t move that arm. With sufficient blood loss, the character goes into shock and may die. If medical technology in your world predates antibiotics and aseptic technique in surgery, infection may finish off the character when the battle does not. Think back to that arrow: it’s likely driven material from their clothing into the wound, a perfect breeding site for bacterial contamination. If a character suffers from a maiming wound, you need to show the effects–they’re not going to toss their sword from their hurt right hand to their uninjured left and keep on swashbuckling (and making snarky quips). Magical intervention may rescue the character in time, but you still need to provide anatomically and physiologically realistic consequences for the injury.

Assuming your character survives the injury, it’s likely to cause weakness, pain, and debility for the rest of their life. You can add conflict, empathy, and verisimilitude to your story if your middle-aged knight suffers from stiffness, lameness, or other long-term sequelae of having gotten banged up on the battlefield.

While we’re discussing battle wounds, here’s a fantasy trope that makes me ballistic: when somebody takes an oath and seals it by slashing their palm with a dagger. Argh! It’s not cool and dramatic–it’s insane. Such a move wouldn’t just cut through skin. You’d sever tendons in your hand and never use that hand again. If that wasn’t bad enough, a laceration that deep invites infection and guess what? You’d lose your hand. Sure, pricking your finger doesn’t seem as dramatic, but you’d still draw blood without crippling yourself, a no-no for warriors and everybody else.

My favorite prevention tip for any situation (not just a fight scene) where you’re not sure about your facts? Research! Talk to martial-arts teachers and fight choreographers (not to mention emergency-room physicians); observe a combat arts class using weapons and techniques from the period that inspires your alternate world. Read about period weapons, strategy and tactics, even armor. Armed with all this knowledge, you’ll find that you can create plenty of drama with your fight scenes without relying on inauthentic, implausible cliches.

Characters Who Challenge You

Elychion the cat wrestling with her gambling, football-watching, and drinking problem.

I didn’t want to write about a drug-addicted surgeon who’d lost his license and resorted to performing illegal procedures in a back alley. But regardless of my intentions, he showed up on the page, told his story, and made me care about him.

Alas, I shelved the novel where he appeared–for other reasons, not because of him. Perhaps he’ll find a place in a different novel, but even if he stays on the shelf, writing from his point of view contributed to my growth in this craft.

Even the most resolute planners among us encounter surprises on the page (or screen). Like meals we hadn’t ordered, characters, props, and plot twists appear without our having sketched them out beforehand. As a dedicated pantser (a writer who does minimal pre-planning, preferring to go with the intuitive flow–and who ends up revising a lot), I’ve learned to appreciate the serendipitous. It doesn’t hurt to let it happen…I can always revise, which, as I said, I do a lot. Perhaps if I were the planning type, I wouldn’t need to revise as much, but my mind just doesn’t work that way, so I take the drawbacks with the benefits to my compositional style.

Trusting to this intuitive, revelatory aspect of the writer’s art, I find that the people who start populating a story are often challenging individuals. Multidimensional and intriguing they may be, but they’d also be difficult to get along with in real life. Prickly, domineering, principled to a fault or charmingly manipulative, engaged in activities I’d find reprehensible–both in writing and in acting, I enjoy rising to the challenge of entering heads very different from my own and then finding the common thread within them that causes me, and hopefully the reader, to empathize with them.

Here are some reasons why I savor the chance to create a difficult character.

Interesting people are often difficult. The other day, I was talking with a patient who observed that her weaknesses aren’t so much opposed to her strengths as they are a flip side to those strengths. I agreed with her. The very features that can make someone accomplished at what they do can also be hurdles to working and/or living with them. (I admire Mother Theresa, but can you imagine living with a saint?)

Let’s say your protagonist’s most salient characteristic is their persistence. They’ve gotten where they want to be through sheer dogged perseverance, and you and the reader can admire them for it. However, the reverse side of persistence is stubbornness, obduracy, even rigidity. They may persist with a battle they can never win, slamming into that brick wall again and again in the mistaken belief that it’s oh so close to crumbling. (Most likely, if it does, it’ll land on top of them and bury them.) A persistent individual may not come equipped with the discernment to know when they’re wasting their stick-to-itiveness on some futile situation where they’ll never make headway.

This virtue/flaw dynamic can make for engaging reading, provided that there’s 1) something there that the reader can identify with (even if it’s in a person they know) and 2) it sets the character up for troubles that generate the plot and keep it moving.

Difficult characters are dynamic. A hallmark of a well-written main or supporting character is dynamism: through the story’s events, the character changes. Characters who are challenging–in terms of personality, beliefs, circumstances, and choices–have more room for transformation than characters who are already self-actualized. (By definition, an enlightened, self-realized character leaves little room for more growth.)

The potential snag here is to allow your character’s sharp edges to manifest without making them so sharp that they’re off-putting to the reader. Here’s an example of how effortful it can be to strike that balance.

One of my favorite fantasy series is the now nine-volume Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever by Stephen R. Donaldson. Back in the late ’70s, long before George R.R. Martin popularized gritty fantasy with the Song of Ice and Fire series, Lord Foul’s Bane transformed the genre with its tormented anti-hero, Thomas Covenant, who appears in a magical Land in the likeness of a legendary hero. The people he meets accord him respect because of this likeness, but they also expect him to save the Land–or why else would he have been transported there? Covenant, however, believes that the Land is an elaborate delusion and giving in to it could destroy his health and life in the “real world.” In light of this logic, Covenant refuses to take heroic, or even principled, actions on behalf of the Land. To the contrary, he harms, sometimes violates, the people who place their trust in him.

As the story progresses, he changes from an embittered, rejected man who lashes out, to devastating effect, to an actively compassionate “doer.” However, I admit that sticking with him on this journey was hard work. To say he started as an unlikable character is an understatement. I couldn’t stand him. I yearned to kick him in the head. For a while, I persisted in reading only because the Land was so enchanting and the other characters so sympathetic.

From my experience with struggling to stay with Thomas Covenant on his quest, I decided that I needed to introduce my difficult characters’ redeeming qualities early on so that readers wouldn’t bail. If my character had a criminal, corrupt, or otherwise morally murky past, I now introduce them to readers at a point where they had already overcome their worst tendencies and only introduce their past crimes once the reader (hopefully) has started sympathizing with them.

This brings up another point:

Characters with hard-to-handle personalities make great antagonists, or at least obstacles for the protagonist. These clashes create internal and external friction that drives the protagonist’s decisions, colors their perspective, and complicates their life in ways that move the plot forward, or at least makes it thicken. Characters with obnoxious personality traits can be balanced by other traits that make them relatable, or at least interesting. This complexity helps the writer to avoid creating one-dimensional antagonists, the kind I’ve described before who, like the Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz, celebrate their own “beautiful wickedness.”

When I’m writing about someone who thinks and acts differently from me, it’s harder to use my novel to advance a political or personal agenda. It’s easy for characters to become mouthpieces and plots to become bullet points in a sermon. I’ve read some fantastic novels that make a point, but what makes a difference between mastery and clunky propaganda is that in the masterful example, the writer’s agenda never dominates over a winning story, intriguing characters, and a stellar writing style. One way to ensure that your novel doesn’t devolve into a pulpit in print, and prevents you from sticking a bullhorn into each character’s hands, is to give at least one of your viewpoint characters a perspective that differs from your own.

What better way is there to start understanding, and empathizing with, someone than to try getting into their head? For me, writing isn’t just a career–it’s also a path to self-growth. As social beings, our growth isn’t exclusively solitary. We grow when other people challenge us, either by encouraging us to hone our best qualities or by bumping up against us in ways that nudge us to rethink our responses, our beliefs, and our decisions. While I don’t advocate turning your family, co-workers, or friends into characters, some of their features can inspire your creations. As you explore what makes such an individual tick, perhaps that deeper perspective can redound in your real-world relationships and help you to understand those hard-to-like folks better.

Writing as an Act of Compassion: What I Learned from Lexus

Photo Credit: “The 4 Differences Between Introversion and Social Anxiety by Ellen Hendriksen, Quiet Revolution, https://www.quietrev.com/the-4-differences-between-introversion-and-social-anxiety/

Every few years, Lexus swoops back into my sedate world. (I’ve changed her name, age, physical description, and life story to protect her privacy.) At six feet tall, with eyes the color of acid-washed jeans, she’s noticeable even without her booming voice and constant jitteriness. She’s in her 20s, but she’s used hard drugs for over a decade and they’ve aged her: her face is gaunt, silver does battle with straw gold in her hair, and the skin on her hands looks glued to her bones.

She jokes that she got her name because she was conceived in the back seat of a Lexus, but I doubt her 14-year-old mother had ever seen the inside of a luxury car. She was first placed in foster care as a baby and spent her childhood going back and forth between different foster parents and her biological mother, who tried repeatedly to get clean and failed. This history of precarious attachments turned her into a youth who tried all the time to charm people into loving and not leaving her. But they kept leaving her. And eventually, she learned to leave them, disappearing for months and brushing off their worries with a brash smile when she returned. When people proved unreliable as love objects, she stumbled into substance abuse. Without someone trustworthy to love her, she could at least recreate the chemical experience of being loved. Yet even the drugs left her, in a way: she’d come down from her high and do desperate things to get more drugs and recreate that sensation of the love she’d not so much lost as never had.

Every time Lexus reappears, I offer to connect her with social services that could help her, particularly those with a harm-reduction philosophy, where she can get assistance first and then contemplate quitting once she’s stably housed. Every time, she turns me down with a smile. “Some time, Mar, some time when I’m ready. But I’m not ready yet.”

Whenever she leaves, I fear she’ll die before she’s ready. I worry about her overdosing, or getting beaten up so badly she won’t recover (and she’s survived many an assault). Every time she says, “Some time when I’m ready,” I’m struck by my powerlessness to rescue her. Here I am with my hand stretched out to take hers and she pulls hers back, smiling, shaking her head.

Sometimes I feel angry that she refuses help. How can she possibly enjoy her relationships with fragile people who only know how to lash out? How can she choose such a tightrope existence–couch-surfing, camping under overpasses, sleeping in cars–over stable housing, work, and community? But then I feel ashamed. After suffering multiple head injuries, she struggles to concentrate, to understand instructions, to read. What types of job opportunities does that leave her? And with a history of misdemeanors and a felony or two, who will hire her?

Neurochemically speaking, her default setting has become “Adrenalize,” so her brain may not distinguish between excitement and terror. That on-the-edge feeling that goes with her teeter-totter circumstances may energize rather than agitate her. Then there’s the solidarity that comes from belonging to a marginalized, neglected community that so many straight-and-narrow people write off as “bums,” “druggies,” “wastes of space,” etc. As dysfunctional as her street-family structure may seem to those on the outside, she speaks about them with affection and loyalty. This family she’s chosen doesn’t condemn her; they offer mutual aid, understanding, and protection in the coldest of situations.

Knowing a person like Lexus has taught me a fierce and wrenching compassion. She’s taught me that sometimes I can’t change all the circumstances I yearn to. She’s taught me that I can’t save people when they don’t want to be saved (and they might take exception to my idea of “saving”: while Lexus sure doesn’t relish sleeping on the street, she also shies away from assistance from people and organizations she expects to look down on her and deprive her of her freedom). I’ve learned that sometimes it’s difficult to tell the difference between empathy and arrogance, between caring about someone and assuming you know what’s best for them. I’ve learned that love remains even if you don’t approve of the way someone’s living their life, and that you can love someone and still protect yourself. (When she’s around, I hide my wallet–protecting us both.)

As far as writing goes, Lexus has taught me to respect my characters, all of them, regardless of whether or not I approve of their value system and their actions. I’ve learned to let the characters speak as their true selves, not as mouthpieces for me and my morals. I’ve also learned to love characters who behave in ways I consider sad, problematic, or even despicable. And I’ve learned to take care with the degree to which a person I know in real life influences the way I describe a character.

Writers have the power to speak on behalf of those whose voices aren’t heard in their societies. Writers also have the opportunity to exploit those vulnerable voices. If they’re not careful and conscientious, they can end up usurping another’s voice, stealing another’s story, instead of fostering awareness among readers who haven’t endured such experiences. It’s tempting to make use of someone else’s story to fill in the expertise blanks, so to speak. If I’ve never flown a plane, fought in a war, cleaned an office building at midnight, or come out of a coma, I can either read about or talk with someone who has and can feel more comfortable putting myself into the head, and the life, of a character who’s done whatever it is I haven’t. We all do this to some extent. It’s part of our natural tendency to connect with others, to empathize, and to share. However, when you’re a storyteller, it’s something you must do responsibly so to avoid degrading further people who’ve already been damaged and exploited.

I’ve always admired William Shakespeare for both his ability to create characters from all walks of life–from an insecure prince to an inebriated guard at the city gate–and to love them all, even if they’re unpleasant, gross, selfish, vain, weighted down by life, fragile and about to break, ignorant, strutting, misogynistic, clueless… I’m sure he had his own 16th-century version of Lexus, and he had the largeness of heart both to present her as she was and to love her, to care about what happened to her, with both unflinching compassion and truth that doesn’t avert its gaze.

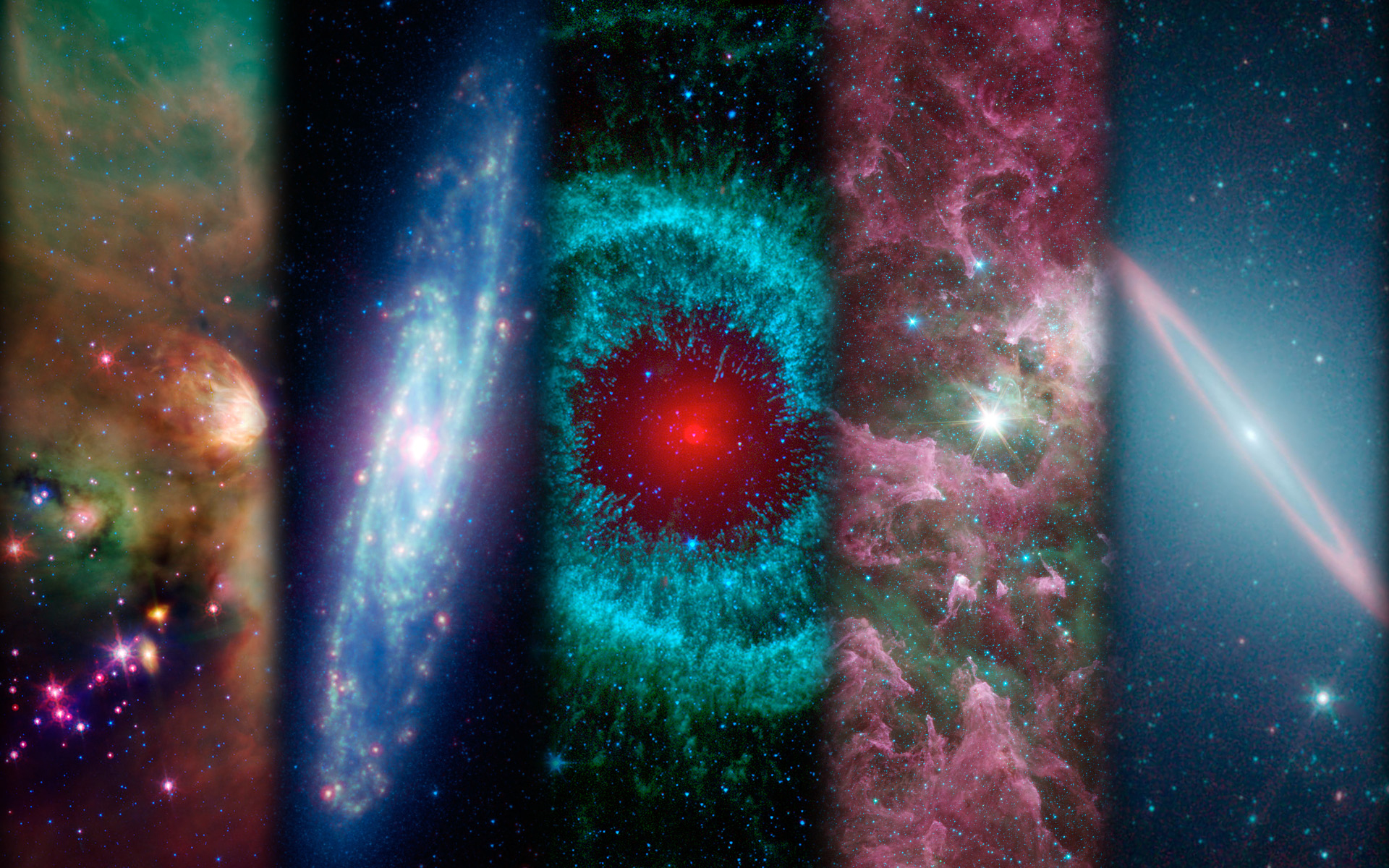

Spacetime of One’s Own

Image from the Spitzer Telescope courtesy of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=3883

As a teenager, I spent much of my free time gaming. But because this happened in the 1980s, when video games were a low-resolution-graphic gleam in designers’ eyes, “gaming” meant tabletop role-playing games, the venerable Dungeons and Dragons and its offspring (anybody remember Tunnels and Trolls?) My favorite magical object with which to equip my characters was the Bag of Holding: on the outside, a simple drawstring bag, but on the inside, a spacetime pocket where the user could stuff any number of weapons, treasures, books, and other necessities. The character didn’t have to bust their back schlepping all these things because the magical storage unit held them, ready for retrieval.

I’d love to create a writer’s equivalent of a bag of holding, not to stow my laptop, but to use as a study only I can access–a room of one’s own, as Virginia Woolf put it in her eponymous 1928 essay, free from distractions or responsibilities other than to the page and the story. I’d also equip my spacetime pocket with a beneficial temporal feature: no matter how much time I’d spend writing in there, I’d emerge at the same time during which I’d entered, with no time elapsed in ordinary space.

Articles and books aimed at aspiring writers encourage, and sometimes chide, readers to make time to write every day. Sometimes they take a scolding “if I can do it, so can you” tone. These advice-givers remind us that they didn’t start out as full-time writers, that they held down full-time jobs, and if they could scratch out a pocket in spacetime to write, what’s our excuse?

I’ve noticed a pattern: these admonishing writers usually describe juggling work and writing, not writing and raising a family and/or caring for elders or family members with disabilities. Having done all of these things, usually simultaneously, my impression is that the work-writing balance is more straightforward than the family-writing balance because most of us work at set hours and don’t take our work home. (Exceptions abound, of course: teachers take papers home to grade; some folks’ homes are their workplace.) Thus, one can schedule writing time as one schedules work. It involves sacrifices for sure–I get up at 3 a.m. so I can exercise and write before work, and to get adequate sleep, I retire at the same time as my six-year-old does–but in settings where everything else finds its place on an appointment calendar, one can make it happen.

The work of caring, on the other hand, doesn’t fit so readily into a schedule. Focused as it is on tasks rather than time, caregiving overlaps temporal boundaries. You know this if you’ve ever scrambled to get to work on time because your preschooler insists on buttoning her own sweater, takes ten minutes when you’d take 30 seconds to complete the task for her, and then becomes overwhelmed with frustration when she finds the tiny holes too difficult to manage and needs another ten minutes for hugs and soothing. When spinning in the vortex of a time crunch, writing time–like any species of “me time”–is the first thing to go.

Small helping hands, courtesy of Self-Sufficient Kids: https://selfsufficientkids.com/kids-chores-how-get-started/

No wonder that, historically, writers belonged to the aristocracy! Somebody else did the laundry; somebody else tended to the children; a whole staff of somebodies made writing lives possible for many a famous literary figure. The English Romantic poet William Wordsworth, for example, acknowledged his wife, his sister, and his sister-in-law–all of whom performed the quotidian deeds that kept him fed and housed in comfort–as “dear hands” who brought food and other necessities. (Not even people–disembodied helping hands!) The wealthy writer didn’t need a bag of holding–they had a room, a suite, a wing of their own and a door to close on familial cacophanies.

Almost a hundred years later, Virginia Woolf’s observation still holds true: to get serious about writing, we require our own funds and our own space. (Although she was talking about women writers, I think her words can apply to people of any gender for whom time-consuming, and unpaid, caregiving takes up a significant portion of their day, and sometimes night as well.) Independence, professionalism, being taken seriously (until one gets not just published but remunerated reasonably for one’s writing, often friends and family treat your “scribbling” as a hobby that can be interrupted)–all of these are boons to writers. And the largest boon of all would be distributing the work of caring for children or elders so most of the responsibility doesn’t devolve onto one person. When one person gets designated “the carer” (especially if that person also works for pay and then comes home to the second shift in the home), writing inevitably gets shelved.

Oxford World Classics’ cover for Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas

Solutions to this spacetime crunch abound, and they’re different for everyone. For some, liberation comes from outsourcing these activities to others: a paid house-cleaner, a grandparent who can take care of the kids for the day on weekends, subscribing to those online meal services where ingredients get delivered to you and you just have to heat them up. For others, it’s worth the sweat and tears to sit down with one’s significant other and hash out a plan for making the home-work load measure up to the 50/50 ideal.